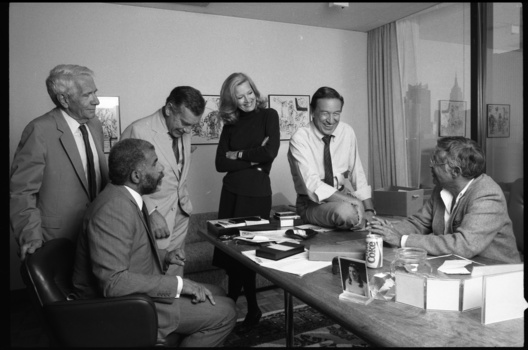

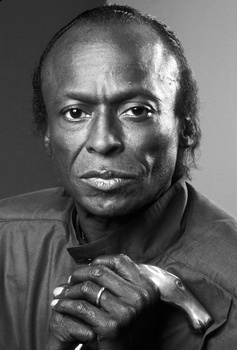

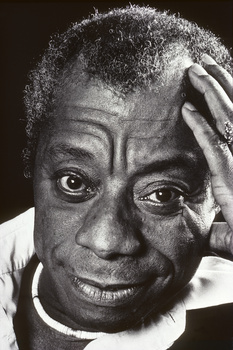

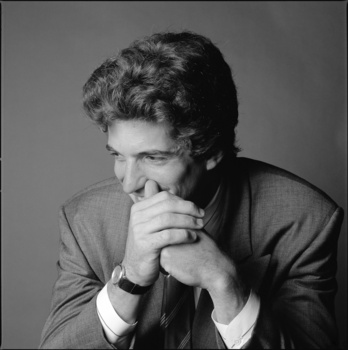

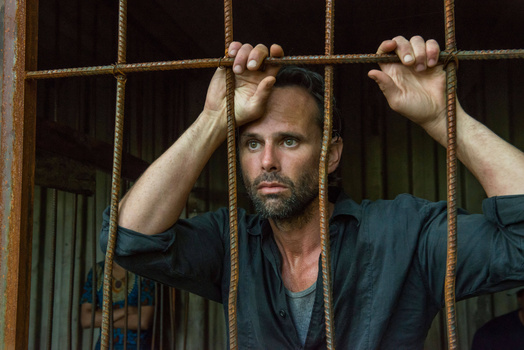

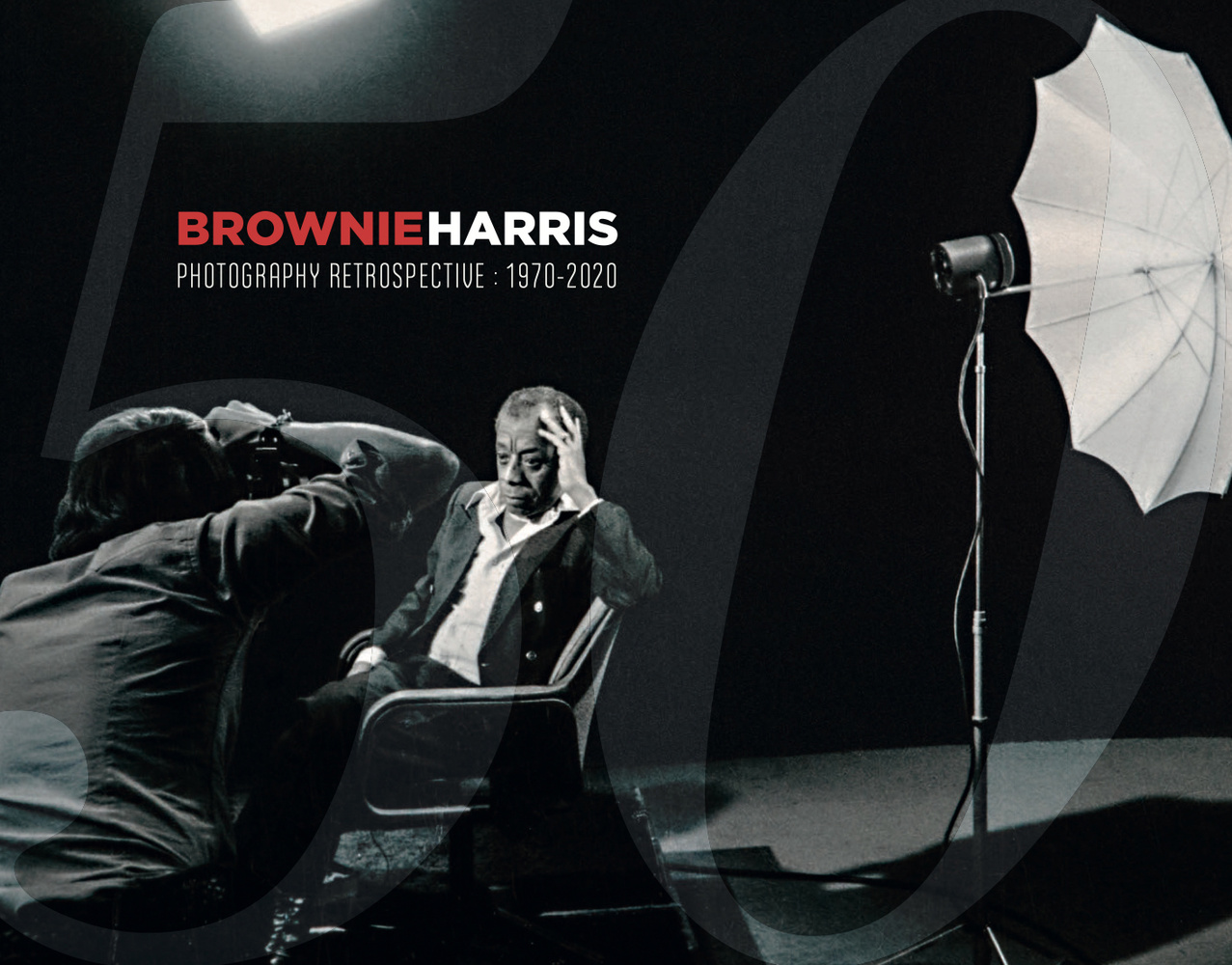

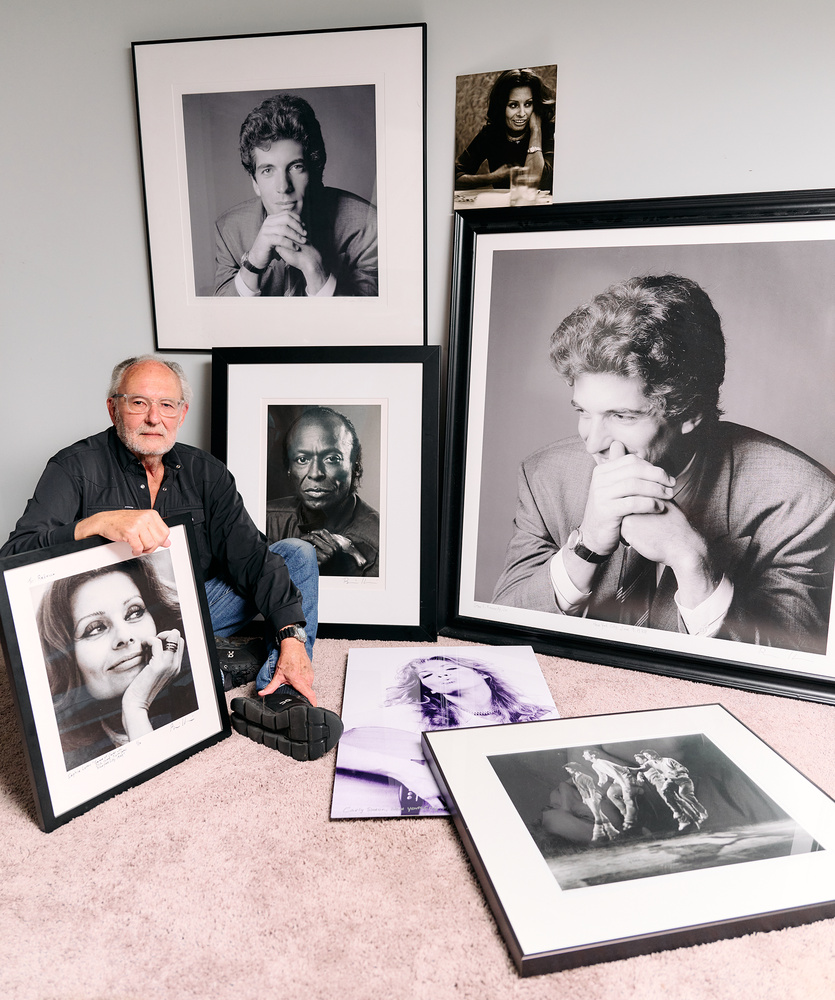

Photographer Brownie Harris has spent five decades capturing both the famous and the ordinary, with a portfolio that stretches from John F. Kennedy Jr. to factory workers and Hollywood sets. Earlier this year, Harris released Brownie Harris Retrospective 1970–2020, a book that brought together a lifetime of images and stories.

The collection spans cultural icons, corporate giants, and everyday life, presented with Harris’ trademark mix of precision and empathy. Alongside the photographs are reflections on the process, the pressure, and the moments that nearly slipped away. The book is less a farewell than a checkpoint, a chance to see what 50 years behind the lens can reveal.

Interview

Your career began with that 1970 photo of a police car with “oink” graffitied on it during a student riot. When you were assembling this 50-year retrospective, how did it feel to revisit that moment that started it all?

Actually, I totally forgot about that photograph until the designer Matt Summers of ProvisMedia mentioned it to me. First it’s been exciting, exhausting, fun, stressful, intriguing, a lot of anxiety and humbling. I hope that other photographers and artists find the urge to create their own book and leave a lasting legacy. If you have a mind to it, you can do anything. In the end, when I saw the finished book proof, I realized how much I had accomplished. So many times in my life, I thought I would never work again. It’s common in the freelance life to think you’re unemployed until the next job.

You mentioned going through “25 or 26 containers of transparencies, black and white negatives and prints” over three years. What surprised you most during that archaeological dig through your work?

I had forgotten how many various people, known and unknown, that I had photographed over 55 years. This process took two years of editing and scanning for Getty Images, for which I am an exclusive contributor. Total amount before edits was over 150,000 photographs. Matt Summers had all the photographs that I scanned for Getty Images on his server, and we both quickly went through thousands to select the best for the book. A lot were left out.

A friend noticed a connection between a photo from 1970 and one from 50 years later, taken just blocks apart, which inspired this book. Can you tell us about those two images and what they represent about your journey?

Strange how 50 years later brought me back to a similar photograph shot only a few blocks from each other.

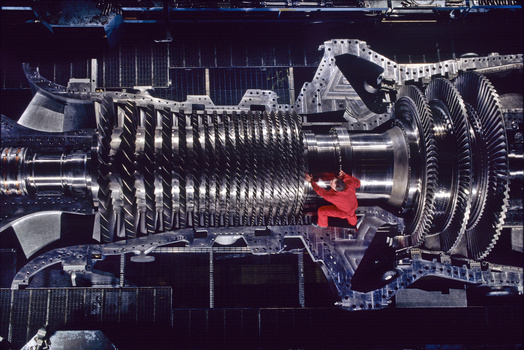

In a previous interview, you mentioned using 27 Dynalite heads for one shot — all in the film era without an LCD screen. How did you develop that technical intuition, and how has your approach changed in the digital age?

I guess you mean the gas turbine photographed for GE. In the analog days, we had Polaroid backs that fit on the back of our cameras for lighting tests. The back was great, as you could use the same camera body and lens that one was actually shooting with. Great invention, but you had to wait two minutes for development, which was difficult hanging 75 feet above the turbine in over 100-degree heat. Now, with digital ones, you can see various lighting situations very quickly.

What’s your mental process when you first meet a subject?

I research every subject before the assignment and then let them collaborate to create the photograph.

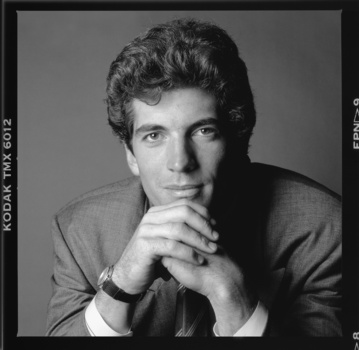

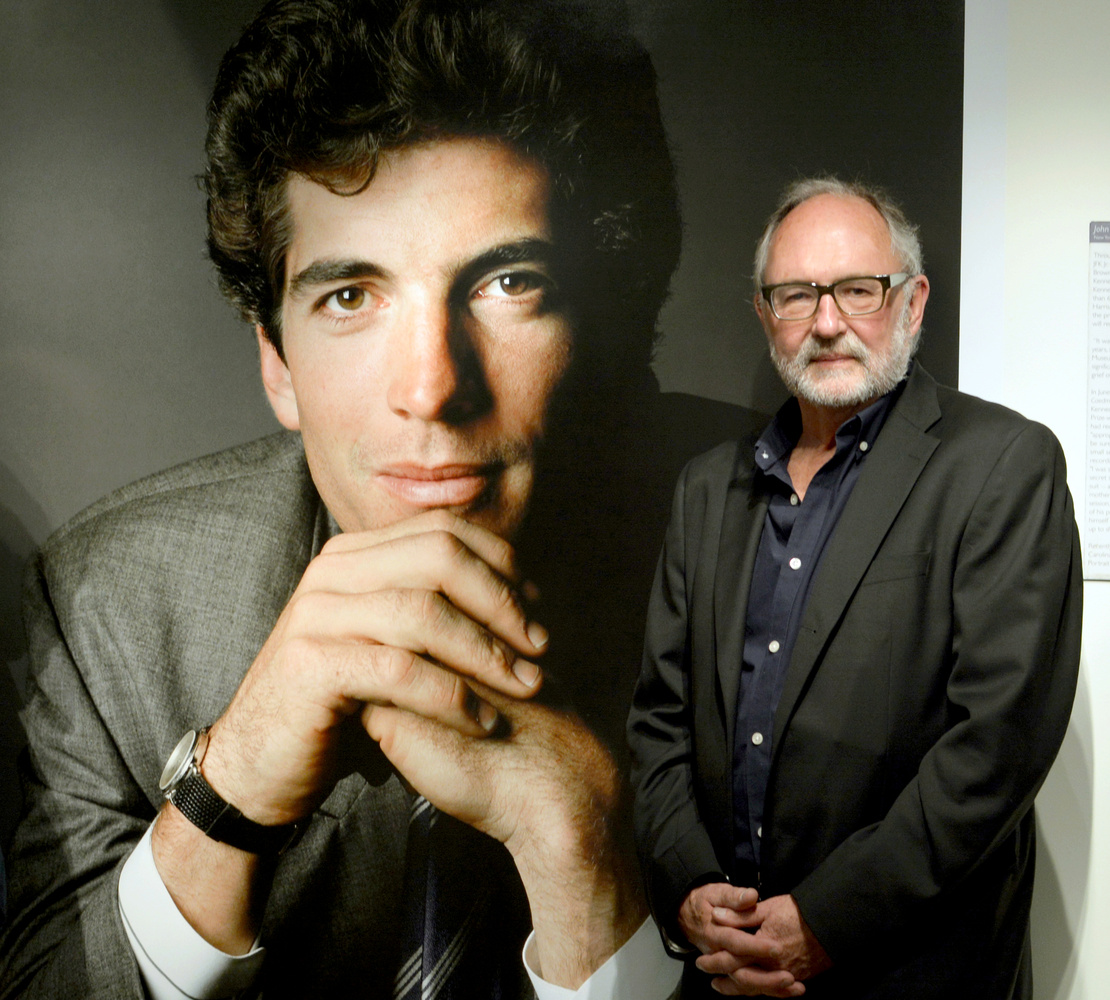

You recently uncovered never-before-seen images from your 1988 JFK Jr. session while going through your archives. What was it like rediscovering those images, and what do they reveal that we haven’t seen before?

When he entered the small conference room, he looked like any 27-year-old kid. What he gave me at the end of the session was what he would look like in the future towards his passing. I was amazed at how many different looks he gave me. He created the photographs. I just shot them.

You’ve said you approach everyone “with the same respect” whether photographing “luminaries of our time or ordinary people at work in factories and on farms.” How do you maintain that consistency across such different worlds?

Well, I must go back to that great quote by Helen Keller: “The best and most beautiful things in the world cannot be seen or even touched — they must be felt with the heart.”

You’ve mentioned “there was always pressure to get the photograph” because missing it could mean never being hired again by major publications. How did you handle that psychological pressure, especially in the pre-digital era?

The pressure is the same now with digital versus analog. Just a different way to be the messenger.

At 22, you created the photography department for WNET/Thirteen in New York, then later moved to Wilmington and worked on sets like Dawson’s Creek, One Tree Hill, and Scream. How did transitioning from corporate and editorial to entertainment photography change your perspective?

It really didn’t because I had already had many years of experience on film and TV sets from 1972 through the 1980s.

Given the resurgence of interest in film photography among younger photographers, what would you tell them about the discipline and mindset required to excel without digital’s safety net?

It’s what you make of it. Whether it’s analog or digital. Embrace any new or past technology. Even AI. Remember when digital came out? Everyone thought that would be the end of photography, when, in fact, it grew exponentially.

After 50 years and this major retrospective, what’s next? Are you discovering new subjects or approaches that excite you?

Right now, just working with the publisher with new marketing and book signing events for the book. The response has been phenomenal. The NBC-TV affiliate here in Wilmington, NC interviewed me about my career and book. Also, The Star News, the regional newspaper, had an article about the book. We had book signing events at The Charleston Library Society in Charleston and another in Kiawah Island, SC. Also I have book signing events here in Wilmington. All the events sold out.

Conclusion

Harris’ story is also a reminder of how photography sits at the intersection of art and work. He speaks about stress, deadlines, and the grind of freelancing, but the body of work that came out of that pressure shows what persistence can do. The camera may have changed from film to digital, but the discipline of showing up, preparing, and seeing people clearly hasn’t.

The retrospective also opens a window onto history in a way textbooks can’t. Seeing Warhol in a quiet moment, a factory worker mid-shift, or a young Kennedy in a conference room ties the cultural and the ordinary together. Harris has lived in both of those worlds, and his archive demonstrates that the line between them is thinner than it seems.

For younger photographers, the retrospective is less a monument and more a toolkit. The lesson isn’t about chasing a career identical to Harris’s but about taking whatever access you have, whether it’s to celebrities or neighbors, and approaching it with respect and curiosity. The technology will change again, but that attitude is the one constant that endures.

For younger photographers, the retrospective is less a monument and more a toolkit. The lesson isn’t about chasing a career identical to Harris’s but about taking whatever access you have, whether it’s to celebrities or neighbors, and approaching it with respect and curiosity. The technology will change again, but that attitude is the one constant that endures.

Fifty years of work also puts the idea of legacy into focus. Harris talks about the fear of not working again, the uncertainty of freelance life, and the surprises hidden in his own archives. That tension is what makes a retrospective matter: the knowledge that the work lasts even as the moments pass.

All images used with permission of Brownie Harris.