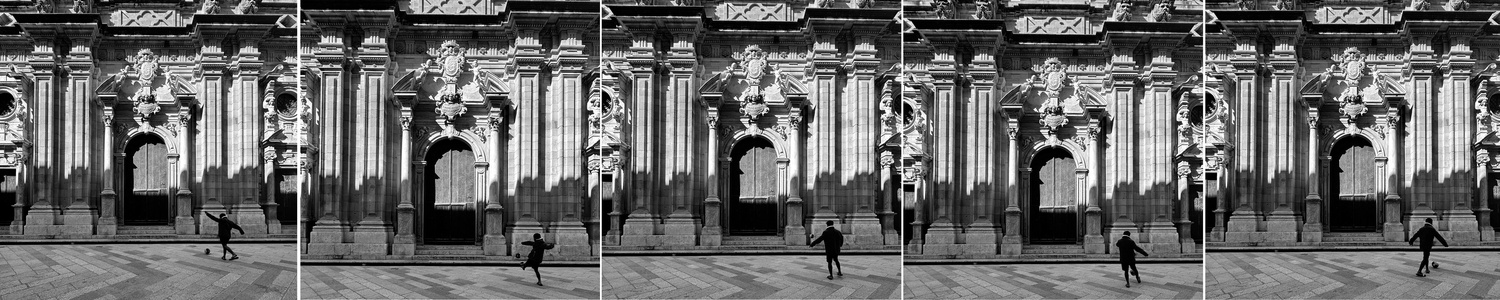

The term "the decisive moment," made famous by renowned photographer Henri Cartier-Bresson, describes the fraction of a second when the significance of an event unfolds in front of the lens. However, in today's "spray and pray" digital age, it begs the question: Has the essence of the decisive moment been lost?

The Decisive Moment in the Age of Digital Photography: A Vanishing Art?

In the age of digital photography, where cameras can squeeze out a growing burst of images per second, some of that magic that photography once held seems to be slipping away. The craft of timing and the skill required to capture the perfect moment are being overshadowed by technological advancements that allow photographers to "spray and pray," hoping that one of the hundreds of images will be the one.

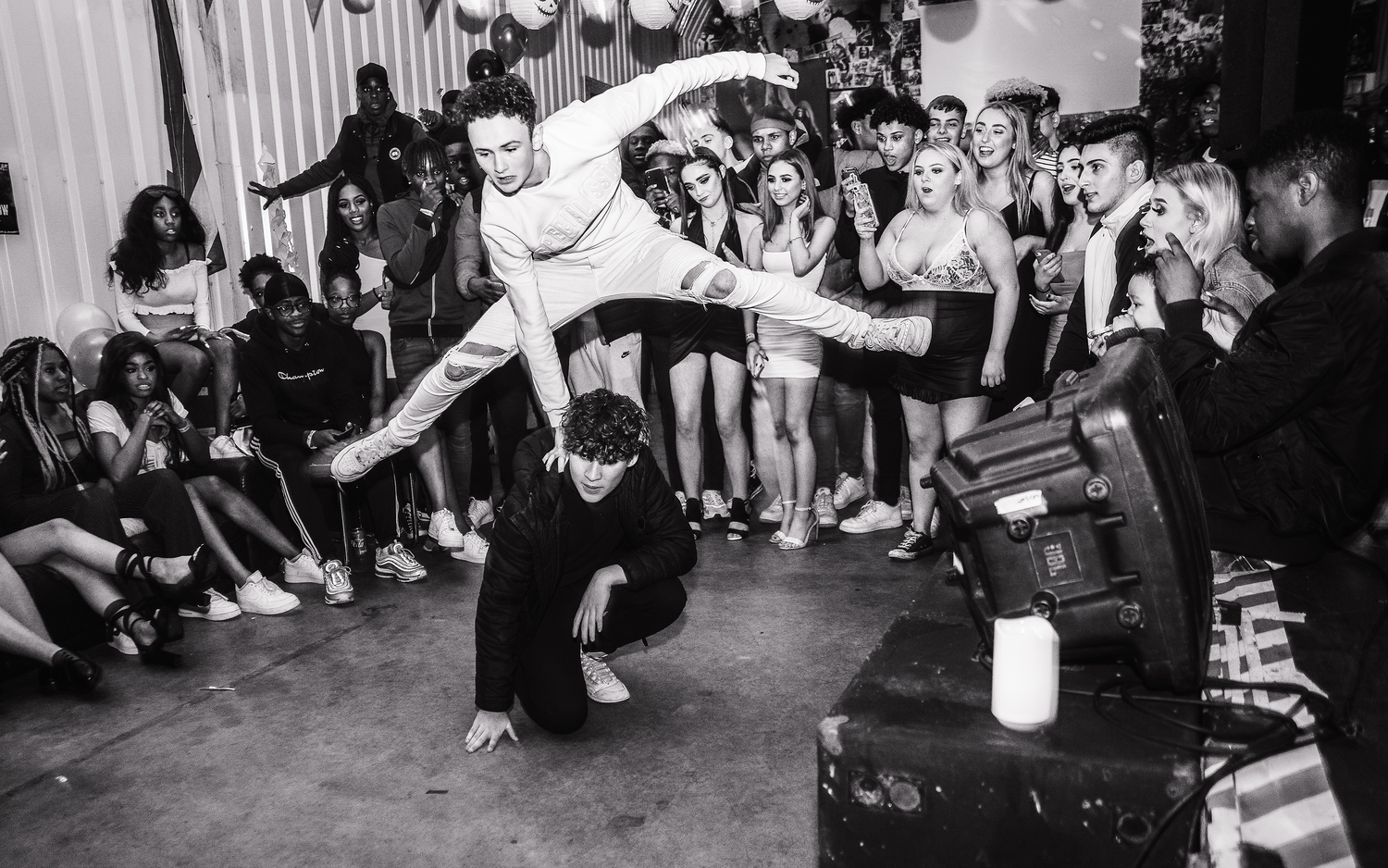

I’m often at events where photographers attend, and the sound of a shutter drilling every time the action changes is quite disheartening. This shift in practice raises concerns about the erosion of the artistry and precision that once defined photography.

The Impact of Technological Advancements

Digital cameras have revolutionized the way we take photos. The ability to capture multiple frames per second, coupled with massive storage capacity, has fundamentally changed the photographic approach. In the past, each shot was deliberate and thought out due to the constraints of film and the cost of development. Today, the near-zero cost (at least at the time of shooting) of taking and storing digital photos means that photographers can afford to be less selective with their timing and more reliant on volume.

Of course, this approach is useful in commercial sports photography, where capturing the exact moment a player scores a goal or an athlete crosses the finish line is crucial for documentation purposes. High frame rates ensure that photographers don't miss these critical moments. However, outside these scenarios, the reliance on rapid-fire shooting can dilute the essence of capturing a well-composed, thoughtfully timed photograph.

The Art of Waiting

One of the most significant casualties of this technological shift is the art of waiting. Photography has always required patience, foresight, and an intuitive sense of timing. I can’t count the number of times I have spent hours in a single location, waiting for the light to be just right or for the subject to move into the perfect position. This patience was not just about waiting but about engaging with the environment, understanding the subject, and predicting the right moment to press the shutter.

In contrast, the modern approach often involves setting the camera to burst mode and letting it run. The result is a plethora of images to sort through, indeed with a high success rate, but this method lacks the intentionality and connection that characterized photography and the art of seeing the moment. The decisive moment is no longer chosen by the photographer but found somewhere in a sea of images.

The Emotional Connection

The magic of photography lies in its ability to convey emotion and tell a story. This often requires more than capturing a visually appealing image; it requires capturing the right moment that speaks to the viewer. When a photographer relies on rapid-fire shooting, the emotional connection to the moment can be lost. The act of choosing the perfect moment to press the shutter is a deeply personal one, involving intuition and emotional engagement with the subject or scene.

By removing the need for this decision-making process, technology has created a disconnect between the photographer and their work. The image might be technically perfect, but it lacks the personal touch that makes photography an art form. Pride in my work is important to me, and if there were a lesser amount of skill involved in capturing the right moment, I’m not sure I would bother sharing them.

The Cost of Convenience

While the convenience of digital photography and high frame rates cannot be denied, they come with a cost. The sheer volume of images produced can be overwhelming, making the editing process more time-consuming. Photographers may find themselves spending more time sorting through hundreds of images than they did waiting for the perfect moment to capture.

Worryingly, this reliance on technology can lead to a decline in technical skills, especially for photographers still in the early stages of their learning journey. Photographers may become dependent on their camera's capabilities rather than developing their own abilities to judge light, composition, and timing. This can result in a loss of craftsmanship and a homogenization of photographic styles.

The Way Forward

Despite these challenges, there are ways to retain the magic of photography in the digital age, but it will take a commitment to artistry over convenience. Photographers can choose to be more intentional with their shots, even when using digital cameras. Limiting the number of times the shutter is depressed and focusing on quality over quantity can help maintain the connection to the decisive moment.

Engage with photography from the past. Go to view exhibitions, watch documentaries, read books on the subject, or look back in your own archive to remind yourself that successful images capturing the right moment have always been possible without keeping your finger on the shutter and hoping for the best.

Setting personal challenges, such as shooting with manual settings or using film cameras occasionally, can help sharpen skills and lead to a deeper appreciation for the art of photography. Embracing the limitations of older technologies can inspire creativity and reinforce the value of timing and patience.

Final Thoughts

The advances in digital photography have undoubtedly brought many benefits. However, these advancements also risk eroding some of the fundamentals of what photography is all about. This photographer thinks that we should strive to retain the essence of what makes photography magical: the ability to capture a single, perfect moment in time.

As we continue to embrace new technologies, it is essential to remember that the heart of photography lies not in the number of images you shoot but in the moments we choose to capture. The decisive moment, with all its emotion, skill, and artistry, remains as relevant today as it ever was. By balancing the benefits of technology with the wider principles of photography, we can ensure that the sentiment of the decisive moment lives on.

Do you think that with advances in photography, we have lost our connection to its roots? Or perhaps you have another take on the matter? I would love to hear your thoughts in the comments.

Good post — a timely reminder about intention and patience in photography. I’d just add one thought in defense of digital:

I don’t think we’ve lost the connection — we’ve simply reframed it. The decisive moment was never really about a single shot. Cartier-Bresson often worked in sequences, mostly because he could afford to. Digital changed that. It leveled the playing field, giving everyone access to what used to be a privilege. In that sense, the roots are still there, only on broader ground.

That is a fair point, if Cartier-Bresson was working with a modern pro body would he choose to set on single or continuous shooting? Something which we will never know I guess.

I don’t think it’s necessary. The number of photographs he’s made speaks for itself. :-)

Modern cameras are crammed full of automated features but I would say it is down to the individual to be disciplined rather than 'the decisive moment' being a lost art. As I shoot in full manual and with manual lenses, whilst I can afford to take more photos with a digital camera, I certainly don't have my finger on the trigger. I still like to be just as disciplined as I was when I used to shoot on a film camera. The intention is still the same whatever camera you are using.

Kim Simpson, the author, asked:

"The Art of Timing: Have We Lost the Decisive Moment in Modern Photography?"

Absolutely not!

All you need to do is to look at the winning entries for each category of the more prestigious wildlife photography contests, and you will see that it is all about timing and decisive moments. The images that capture the action or behaviour at the perfect moment win and/or place very highly in such contests, and the images that are more static usually don't place nearly so well.

I addressed this in the article. People who "spray and pray" rather than wait for the right moment, will catch the moment, but the skill and educated guessing in the timing involved is washing away. Picking the best image out of 12 taken in close succession can certainly win competitions too, its just a shame that photographers who shoot just one of that moment - choosing one exact moment to press the shutter - are now fewer and far between.

I understand what you are saying. But to me, the thing that matters is whether the photographer captures that decisive moment, or misses it. How he/she captures it is not important to me. The process of photography is not very important, because the results are what matter. The images that we produce really, really matter. How we captured those images ..... simply does not matter very much. Results are far more important than experiences.

There is usually not just one moment in an event that can result in a great photo. If a deer is running in front of me, I would much rather get 3 or 4 great images than just one great image. In fact, to come away from a stellar opportunity like that with only one great frame is usually a bit of a disappointment, when I know that there were more great moments that could have been captured.

Quality matters, but so does quantity. And there is NOT an inverse relationship between quality and quantity. It is NOT like we could either capture 5 very good images, or 1 truly great image. It is possible, in many action sequences, to capture several truly great images.

As a wildlife photographer and one whose photo was selected as one of the best submitted to Macaulay Library a few years ago, I disagree. In that particular photo, I was watching the eagle for a while, and saw it start to move. I thought it might flush and so began shooting as it shifted its position. Rather than flee, it puffed up its body and raised its crest. Briefly. I think I was shooting 12 fps. One frame only had the crest fully raised.

It isn't just that you don't get that shot with a single click of the shutter, it's that this metric doesn't capture intentionality. The eagle had been perched for several minutes. I didn't take 3,000 shots of it or even 300. I waited for what I knew would be a "decisive moment" and probably took 30 shots to capture the one.

Yes, it was "easy" to select that from a sequence. But I was also not alone that day. No one else got a picture of the eagle with its crest fully raised. That is the measure of intentionality -- understanding your environment, your subject, and knowing when there is a compelling image about to present itself. A high capture rate may help you capture the moment, but the most advanced camera in the world will not be able to tip you off to the clues that it is all coming together.

And as others have mentioned, Cartier-Bresson and all the greats shot a LOT of images. The decisive moment was defined as often in the reviewing contact sheets as it was in the moment. Ansel Adams similarly said a crop of 12 (maybe 24?) good pictures a year was a great achievement. He didn't say only take 12 pictures a year. And very few of his famous images as the only shots he took of his subject that session.

Very well said, David. This idea of the old time photographers waiting for a perfect moment, and then releasing the shutter just once, at the perfect instant, is a myth. As you say, they shot as much as possible and then selected the best image from a contact sheet.

I found this article interesting after looking a dozens of street photography photos posted to Flickr. I have come to the conclusion that many "street photographers" cannot recognize a decisive moment. How many photos are needed of people walking down a street? As suggested in this article, I suspect technology may have played a role in allowing some photographers to become less concerned about why they are taking a photo than in the experience of carrying the gear and fixating on its technology.

I would say there's only about 20% of photographers, unless you have been around the block awhile you use intent in their photography.

Perhaps in street photography, which is not my genre, but far less so in landscape photography which is. One of my best friends is known to wait an entire day in one place for the light and clouds to be in just the "right" spot for his photographs. A bit extreme for me but waiting is part of the game for us.

Your friend is a kindred spirit!

With wildlife photography, waiting is so important. That is why I plan as many days as possible in the field, when I schedule wildlife photo trips.

I spend the entire month of November photographing the Whitetail Deer rut, because it often takes the entire month to find opportunities that are "just right".

Or, when I find an active bird nest in a tree cavity, I will return to shoot there every day until the baby birds fledge, because it often takes 5, 10, or 15 days of shooting to get an image in which everything in the frame is perfect.

With your friend who photographs landscapes, I presume that not only does he wait all day for a moment where everything is just right, but that he returns to the same scene day after day after day, because it usually takes far more than just one day of waiting for everything to line up the way one wants them to.

I grew up admiring the skill and determination of so many National Geographic photographers. I am in awe. Many photographers on this site show enormous skill. I love wildlife photography and over the years have taken a handful of good decisive moment photos. And a small number of those were happy accidents. A vast majority of them were the result of planning, waiting and visualizing the decisive moment. I would love to have been selected to shoot for GA but timing and circumstances prevented that. I like to tell the students I teach ( I taught photography and imaging at Apple for 5 years) that the main difference between them [serious experienced wildlife photographers] and a National Geographic photographer was the willingness to travel to the steaming jungles of Borneo, hike 15 miles, wait 5 days in a mosquito infested blind, brave stinging insects to take 30 rolls of TriX. The goal is to get 30 images for the article. If they get a truly exceptional they me get on the cover.

Very few people are willing to do this, but aspiring to this level of excellence is a good learning experience. My Nikon D600 can shoot quickly and I love that for sports. But I love the challenge and learning opportunity of aspiring to shoot fewer photos and planning more.

Wildlife photographers such as yourself are a very patient breed. I could never do it but I applaud those who do.

A great example of this is Cezanne. He painted the same mountain scene near his home repeatedly over many years. All of them are different and all of them are considered masterpieces.

I agree with you in large part, but I also feel you can have a similar intent without the dedication to constantly returning. Often times when I am shooting wildlife (and to a lesser extent, the landscapes I am in), I adopt a travel photography or documentary mindset. This is how I experienced the landscape on that day. Or this is what I observed of the bird that day.

Of course, in those situations I still want to create a compelling and engaging image, and not what I usually call a "documentary shot" to merely show photographic proof of the bird. Or "look, I saw Mt. Fuji!" But it is also knowing that while it may not be the best possible image of the landscape or the animal, I did capture the sense of place on the day.

And yes, often I leave quite envious of those who do have the opportunity to return frequently to capture the scene over time...

Viewers of our craft really don't care about our "emotional connection". They just want to see great images. For me to hang around forever waiting to capture the perfect timing of an image does'nt make much sense (most of the time). How many countless times was a shot blown while shooting film due to an eye blink or an object suddenly appearing in the frame? Then motor drives appeared. I say fire away.

'Viewers of our craft really don't care about our "emotional connection" '

That's a bit of a sweeping generalisation. How do you know they don't care? Sure I imagine the vast majority of people viewing photographs on Instagram probably spend a few seconds before hitting the like and or moving on but if people are looking at a body of work in a gallery or a book for example, they can spend much more time studying the images and may start to notice a distinct style and also may start to get a feel for the emotional intent behind a photographers work. At least a perceived emotional intent which is still valid.

For me, its not so much about what the viewer thinks. Its about my own experience, my own connection to the subject or scene in front of me. If it is about prioritising the viewers experience then sure, fire away.